Art where you wouldn’t expect to find it.

Let’s begin this episode (Part 2 of ‘We keep getting back on the bus’) with a quiz – ‘cuz why not? Here’s the question: In which of the following places here in The Land would one be likely to find an art museum?

- Atop Har Halutz (where The Levines live)

- At the northbound rest stop on route 6 (next to the Chabad trailer)

- On the grounds of the historic Kibbutz Ein Harod

- In the alleyway outside Power Coffeeworks on Agrippas St. in Jerusalem

Are you surprised that the correct answer is #3? Would you be more surprised that the Mishkan Museum of Art is the oldest art museum in Israel? Would you be even more surprised that the museum is a National Heritage Site and is considered one of the three top art museums in the country? OK then, how is it that I never heard of it before? That’s my question. For that one, I have no answer, but there you have it. That’s the reason for these Study Trips, so you might learn something amazing to share with invited guests around a Shabbat table.

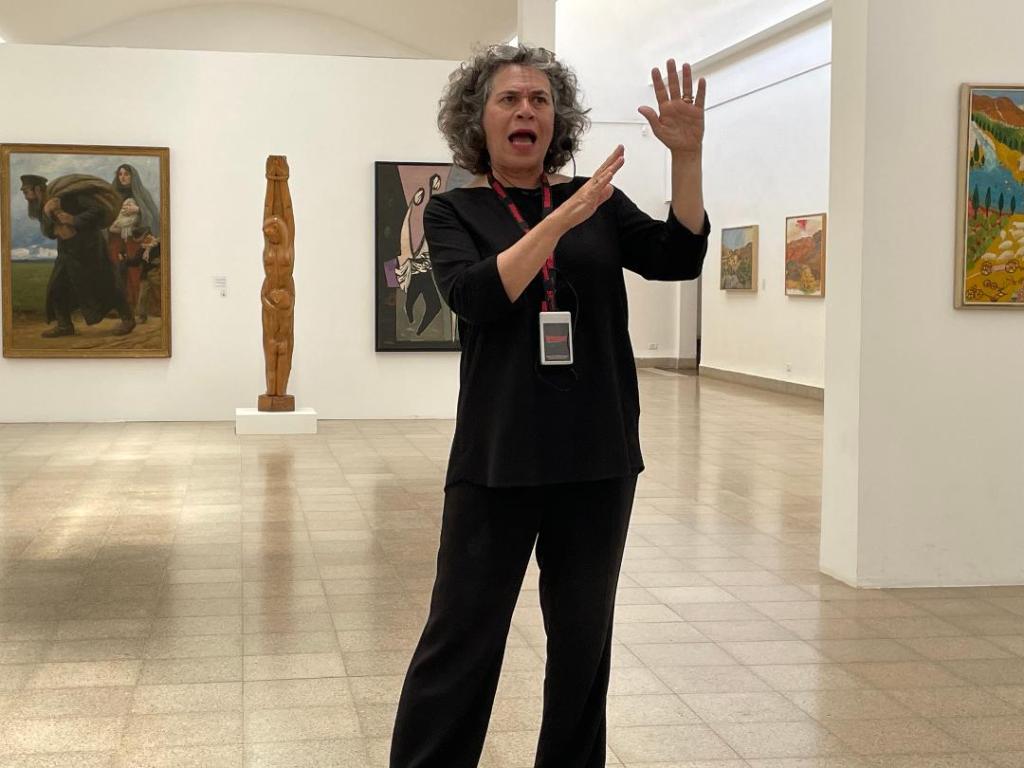

There we were, being ushered into the museum, where we would be guided by Deborah Liss, the curator of their Judaica collection. She had arrived in Israel as a starry-eyed young person with a background in Art History and began working at the museum thirty years ago. (Thirty years ago? Did you study Art History in kindergarten?, I asked her. But then, at my advanced age, almost anyone under fifty looks like a recent high school graduate.)

No matter, there was work to be done. Standing in the main gallery, she first gave us a general introduction to the museum and its collection. (‘Standing’ doesn’t do her justice; perhaps ‘gliding,’ dancing,’ ‘moving to the rhythm of her speech’ would be more to the point.) The main exhibit on display when we were there (they do change their exhibits from time to time, plus they were in the process of reimagining, reconceptualizing how to use their space) was a potpourri of work by, shall we say, mostly not-as-well-known Israeli artists who are deserving of quality wall space to show their stuff.

Then we headed to the curator’s pride and joy, the Judaica gallery. The museum administration had noted, over the years, a general lack of interest in their collection of Torah covers, parochets (the curtains that are hung in front of the arks where the scrolls are kept), and the other paraphernalia found in your standard shul. Of course, if you can see similar items on display in your standard shul…? (I’ll be waiting in the bookstore, Martha.)

Why not mix it up a bit; do a little compare-and-contrast; intersperse the tried and true with some more contemporary items in serious need of display time? Here’s a fellow who took some of his late father’s effects (shirt collars, ties) and made them into Torah covers. That’s different; I like it.

But what Ms. Liss wanted most to talk about was an old parochet that, if I were just walking by, I wouldn’t have given a second glance. It’s quite large – meaning it was made for a large aron kodesh in an impressive synagogue. But look what it says about itself. I was donated to the xxx synagogue in Wurtzberg, Germany in 18xx by so-and-so, the son of what’s-his-name and his wife, what’s-her-name. This large piece of red cloth was among the kazillion items stolen by the Nazis, some destroyed, some kept as a reminder of the chutzpah of the Master Race. Many of these ‘souvenirs’ were repatriated by the Allies in 1945 and distributed among Jewish organizations in Israel and the Exile, which is how this parochet came to Ein Harod.

I imagine that every art curator worthy of his/her name is also a detective of sorts. Given the information carefully provided in Hebrew letters, what more can we find out about the provenance of this parochet? It’s from Wurtzberg; if nothing else, they keep good records in that part of the world. Our fearless curator contacted a German source. You’re reading it wrong. It’s not so-and-so, the son of what’s-his-name and his wife, what’s-her-name. It’s so-and-so (the son of what’s-his-name) and so-and-so’s wife, Mrs.-so-and-so. That’s different! With that emendation, the Gentile lady in Germany was able to figure out who was the generous donor. Most likely, the donation was made in honor of the birth of a daughter, the so-and-so’s tenth child. As a bonus, the source was able to do a little genealogical research. There may be a very distant relative alive in Israel today. That’s quite a story, one I would not have heard if I were on my own, wandering on an afternoon through the museum. As I’ve said before, that’s the value of these trips.

We meet more women named Deborah along the way

When we walked into the Emunah Children’s Home in Afula, we were met by a Deborah and a Debbie, both officials of the organization, who welcomed us effusively. We were one of the first post-COVID groups to visit the facility. (I see they have set out a little spread for us, but didn’t we just have lunch?) However, it was Shlomie, the person in charge of the facility, who gave the main presentation. Whether or not he had planned to talk about the specific situation, it was definitely on his mind. Years before, a man had killed his wife, the mother of his eight children, all of whom were placed in various foster facilities, which is how the boy in question arrived at the Children’s Home. He stayed there for a number of years and was adjusting well; he had been selected for a pre-army program that would assure him a spot in a prestigious IDF unit. Then, just before graduation, he fell apart – who knows why – and started to act out big time. He had to leave the Home and go elsewhere. Everything was going wrong for him. Ten minutes before our group arrived, however, he showed up at Shlomie’s office. At least for the moment, the young man was back on track. Let’s hope.

What Shlomie emphasized – although he didn’t have too (at least for me, who spent twenty years working in Child Welfare in NYC) – was that the boys and girls who reside at this facility or are in their after-school programs are not just random kids off the streets. Every one of them has had something terrible, something tragic, something abusive, happen to them in their young lives and would need a lot of support and intervention to overcome their childhood disasters.

We would get to meet some of these young people. There would be both a baking and a woodworking workshop, and we could participate in either one. For most of the couples in our group, the guy left to go elsewhere for the woodworking session and the wife stayed where we were for the baking. But you know we’re not normal. I flunked woodworking in J.H.S., and it’s been all downhill ever since. I stayed put, hoping to get some photographs to share.

About a dozen girls, ranging in age from –I’m guessing – eight to fourteen came in and sat down on one side of a long table, with our women, all of whom are mothers and grandmothers, sitting facing them. Both sides pitched in and rolled the prepared dough into cookie-sized pieces, which were taken into the kitchen and baked. (Yum!) I have a few excellent shots that I’d love to share of the interaction between these young ladies and our somewhat older ones, but we were admonished: NO SOCIAL MEDIA, so I can’t. One thing you would notice right off the bat is that these girls – and the other boys and girls we encountered playing ball outside – don’t look like the victims they in a sense are, which I guess is the point of the program. Those of us who had gone out to watch the woodworking came back with souvenirs: little wooden boxes. That’s OK; we got cookies. I couldn’t help but remember my failed attempts in Mr. Dicristofaro’s shop class back at J.H.S. 80. That was almost seventy years go – but who’s counting.

Sami Sanchet, front and center

A few Study Trips ago, Sami Sanchet got the assignment to ferry our group around. Our travelers were so impressed with his driving and his helpfulness that they asked, insisted, demanded, that he be the regular driver on all future trips, which is what has happened. When he’s driving our group, he leaves his home in Kafr Manda, an Arab village in the Galil, at some insane hour in the morning, drives down to Jerusalem so we can board the bus and be on our way by 8 AM. He’s with us the entire time. When our four day excursion is over, he drives our group down to Jerusalem and then drives back to his home up north. That’s a lot of driving, but, as he told us, for him it’s easy.

Make of it what you will, but usually at breakfast and dinner at whatever hotel we’re staying at, the bus driver – whoever he might be – usually sits by himself, maybe with another driver, once in a while with the tour guide. This trip, Barbara, being the special person she is, invited him to join us for some of the meals. So we got to learn a little about his life.

For many years, he made a good living printing patterns onto fabrics. And then….. Remember my reference in Part 1 to the large we’ll-steal-whatever-you-come-up-with nation in the far-east. You guessed it; all the work in this industry headed their way, and Sami was out of a job. For most of us, driving a bus is not anything we would choose to do – especially driving the length and breadth of The Land for days on end. (For one thing, you’d need a better bladder than I have.) But, as Sami said, for him it’s easy.

On the last trip (#182), Sami suggested to the powers-that-be (a/k/a Jeff Rothenberg) that on the next visit to the Galil we visit his village. Now that’s different. Just about everywhere we go on these trips, there will be other busloads of people seeing the same thing – if not exactly when we’re there, then sooner or later. But who gets a guided tour of Kafr Manda? The offer was duly accepted, and off we went.

Kafr Manda, for those who are interested, has been part of Israel since the very beginning (think 1948), and its residents, from what I’m told, are reasonably satisfied with that arrangement. The person doing the telling was Mahmoud, a brother of our driver, and the principal of one of the middle schools in the village. Sami, after giving us a short ride around the town, pulled up his bus in front of the school. From my seat, I could see the Israeli flag fluttering on a pole atop the building. We were met by a few of the teachers, including the English teacher, a conservatively dressed Arab woman, who actually spoke decent English. (Unlike the Russian woman who taught The Levine’s son Ari in years gone by, whose English was as good as my Hebrew.) We were ushered inside into Mahmoud’s office and from there upstairs to a classroom – unfortunately empty. (We were supposed to meet some of the students, but there just wasn’t time for that.)

Mahmoud, who doesn’t have a background in education, was brought in several years ago to straighten out the school, and he evidently has done that. Eighty percent of the kids in his school pass their ‘Bagruts.’ The building looks in a lot better condition than the schools we go to in Ma’ale Adumim to vote. (Sadly, I can see another such visit coming shortly.) The principal told us that if there is something he needs from the Ministry of Education, he can pretty much get it. The funding arrangement has been changed; all the money for the school comes directly to him instead of to the village administration – so no sticky fingers get in the way.

When Mahmoud was done, it was time for questions. Actually, one of the questions came from the English teacher. Why did you come here? Well, Sami invited us and drove us to your doorstep, that’s why. But could we give a better answer than that? My wife accepted the challenge. She pointed out that we are surrounded by Arab villages, but we never get to go to any of them. (What she didn’t say was that there are big red signs with white letters telling one and all that it would be dangerous for Israeli citizens to set foot within.) Here was our opportunity to see how our neighbors live. Point well taken.

I had hoped to ask a question, but, again, there just wasn’t time. One woman we know teaches in a school in Ma’ale Adumim. She is constantly frustrated by the lack of discipline in her school. Every parent here ‘knows the mayor,’ and if there’s a problem with her little darling, the parent will threaten you. (There are often attempts to solicit people like moi, who are qualified to tutor English in local schools. Are you nuts???!!!! You couldn’t pay me enough to deal with Israeli teenagers. The best performing school in Israel year after year is in a Druze village somewhere up north. What’s their secret? They don’t take any b.s.; not from the students, not from the parents, so the kids learn. Simple.)

I was wondering how they deal with discipline in Mahmoud’s school and what kind of problems they face, but, again, there just wasn’t time to find out. Sami’s family was preparing a modest spread for us, which turned out to be enough for lunch. He had worked with Aliza to make certain that we could eat everything –no glitches, no embarrassment. We sat in the yard next to Sami’s house. (In typical Arab fashion, he and his wife occupy the first floor, with the second floor reserved for a son when he comes of age.) Were we in an Island of Sanity in a troubled world? Perhaps. If only good will were as contagious as stupidity; we’d all be better off.

Just as every other Study Trip we’ve been on, this one was coming to a close. We first bid farewell to Aliza, our tour guide. Her husband was meeting her along the way, and the two of them were heading down to The Gush for a wedding. As I mentioned, Sami would drop the group off in Jerusalem and head back up north to Kafr Manda. He thanked the group for coming to his village and for inviting him to join us in the dining room. I began to realize how much these gestures meant to him. He wasn’t just somebody driving a bus; he belonged. Isn’t that how all of us want to feel – that we’re not some random stranger, there to do a job and then goodbye? That we belong? That we’re Somebody? Food for thought.